Long before cryptography became a mathematical discipline or a feature built invisibly into everyday technologies, it was a social practice tied closely to power. The ability to conceal meaning was never neutral. It was a privilege exercised by rulers, generals, priests, and diplomats, and later defended as a matter of state survival. To understand modern cryptography, it is necessary to begin not with algorithms, but with authority.

Secrecy before maths

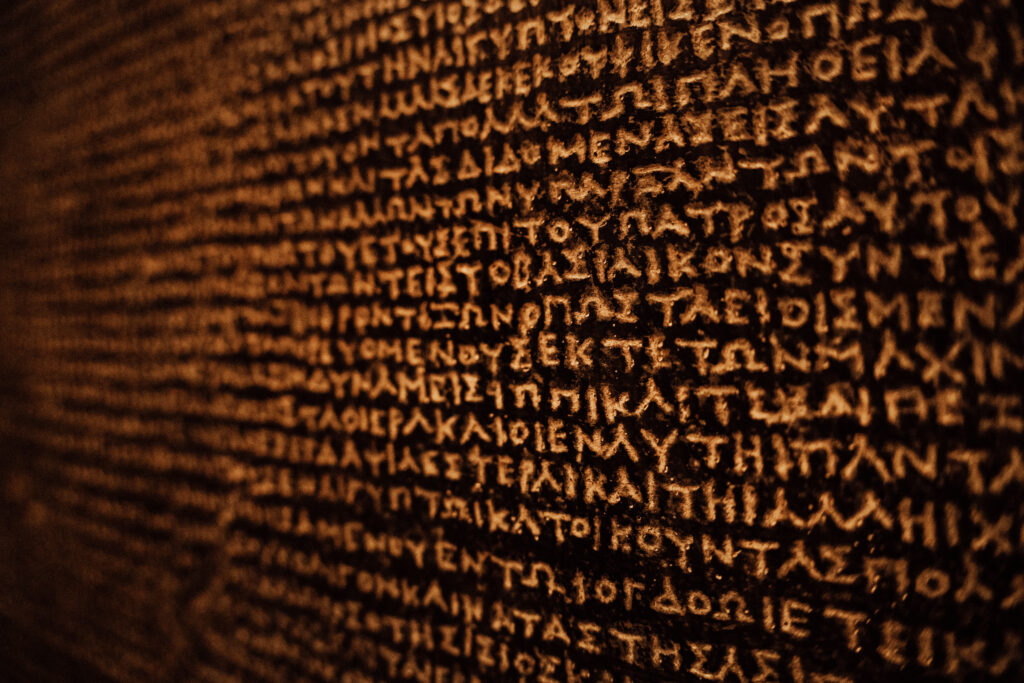

The earliest known uses of cryptography were not concerned with abstract security models or formal proofs. They were pragmatic solutions to a simple problem, how to communicate without being understood by the wrong audience.

In ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs were sometimes intentionally altered or rearranged in religious inscriptions, not to hide meaning entirely, but to restrict it to an initiated class. The goal was not secrecy in the modern sense, but exclusivity. Knowledge was protected by obscurity, literacy barriers, and social hierarchy.

Ancient Greece introduced more mechanical approaches. The Spartan scytale, a wooden rod around which a strip of parchment was wrapped, allowed messages to be read only when wrapped around a rod of identical diameter. This was not sophisticated encryption, but it reflected an emerging awareness that secrecy could be enforced through physical constraints rather than trust alone.

The Roman Empire refined these ideas for administration and warfare. Julius Caesar’s substitution cipher, shifting letters by a fixed number, is often presented today as trivial. In its time, it was sufficient. Literacy was limited, interception was rare, and speed mattered more than theoretical strength. Cryptography functioned as a practical barrier, not an impenetrable one.

Cryptograpgy as a state monopoly

As states became more centralised, cryptography followed. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, diplomatic correspondence expanded rapidly. Italian city-states, the Vatican, and European monarchies developed cipher offices, employing specialists to encode and decode sensitive messages.

At this stage, cryptography became institutional. Codes were no longer improvised by individuals. They were designed, managed, and guarded by states. The secrecy of the method itself became a strategic asset. Revealing a cipher could compromise entire diplomatic networks.

This period also marked the beginning of a crucial asymmetry. While rulers relied on cryptography to protect communications, those same rulers invested heavily in breaking the ciphers of others. Cryptography and cryptanalysis developed in tandem, driven by political competition rather than intellectual curiosity.

Knowledge as a threat

One of the most important developments in early cryptography came not from Europe, but from the Islamic Golden Age. In the ninth century, the scholar Al-Kindi described frequency analysis, a method for breaking substitution ciphers by analysing letter patterns. This was a turning point. Cryptography could no longer rely on secrecy alone. It faced systematic attack.

The implications were profound. Encryption was no longer just a clever trick. It was part of an adversarial process. From this point onward, cryptography became a field defined by tension between concealment and discovery.

Yet even as techniques improved, access to cryptographic knowledge remained tightly controlled. Cipher manuals were guarded. Training was restricted. In many cases, the very existence of a cipher system was treated as classified information.

Cryptography was understood as dangerous knowledge. In the wrong hands, it could undermine authority.

The social function of early cryptography

What these early systems share is not technical sophistication, but intent. Cryptography served three overlapping functions.

First, it enforced hierarchy. Only certain people were allowed to communicate securely. Second, it protected political continuity. Messages about alliances, wars, and succession were existential matters for states. Third, it externalised trust. Instead of relying solely on loyalty or honour, cryptography introduced technical barriers to betrayal.

Importantly, cryptography did not eliminate risk. Messengers could be captured. Keys could be compromised. Codes could be broken. But it changed the balance of risk, making secrecy a managed resource rather than a matter of personal discretion.

A pattern that persists

Although the tools have changed dramatically, the underlying pattern remains. Cryptography emerges where power needs protection. It spreads when communication networks expand. It becomes controversial when it escapes institutional control.

Before computers, cryptography belonged to elites. It was expensive, specialised, and embedded in political structures. Ordinary people had little need for it, and even less access.

This historical reality matters because it frames the conflicts that emerge later. When cryptography moves from courts and armies to citizens and devices, it does not simply become more efficient. It becomes political.

The story of modern cryptography begins here, not with silicon, but with secrecy as a form of power.