The defining characteristic of cybercrime is that the criminal activity rests upon Internet-connected technology. The Internet is, after all, a set of informational protocols enabling computers to communicate with each other. So, how did it affect criminal activities so vastly? We have found the answers in David S. Wall’s “Cybercrime” body of work.

The globalization effect

In the networked world, no island is an island.

McConnell International, 2000:8.

The Internet has contributed to the acceleration of globalization. For the average user, that means you can connect with people worldwide quickly and cheaply, as if they were in the same location. For crime, it means that crime opportunities exist across cultures and jurisdictions, creating new criminal scenarios.

A new division of criminal labour

The most profound transformation that the Internet has brought to its users is the power that it gives them. Lone offenders can exploit networked technologies to carry out complex tasks that can be automated and replicated globally. These tasks, which before could only be carried out by organized groups with financial and organizational means, are now limited only by bandwidth and language.

This changes the dynamics of the criminal activity’s Return On Investment, making offending more cost-effective. Criminals can commit smaller-impact, bulk victimization across a broad geographical span, and they don’t even have to obtain a high success rate to break even. Besides, because they tend to work alone and remotely, their chances of getting caught are reduced because there is little criminal intelligence about them.

The law doesn’t concern itself with trifles

De minimis non curat lex.

(Unknown)

For the justice process, these new dynamics of crime have a considerable impact: small or low-impact multiple victimization distributed across many jurisdictions can constitute a significant criminal activity. Yet, individually, these crimes don’t justify the expenditure of resources in investigation and prosecution.

The swarming model

Another considerable effect of this new criminal setup is that offending groups with different skill sets have begun to collaborate: hackers, virus writers, and spammers are providing specialized services to each other across the Internet. Rather than replicate traditional organized crime models, such as gangs or hierarchical “Mafia”-like structures, individuals with different skills will respond to demand where and when needed. Individuals will cooperate temporarily to achieve specific objectives and, upon success, go their separate ways.

These transient criminal organizations are starting to exploit this model to target much higher objectives. Organized groups are spreading a high-tech crime wave around the world in seemingly random patterns, targeting individuals, corporations, and Government organizations.

The deskilling effect

The deskilling effect originates from Marxist theories, which aim to break down complex tasks into essential tasks and automate them to make them more efficient and cost-effective. A typical example is the assembly line, where machines have replaced humans to execute repetitive tasks. While these tasks are degraded and de-skilled, a simultaneous re-skilling process occurs when workers take control of these automated production processes.

The same happens with criminal labour. One person can now use a computer to control a complete set of processes running on networked computers to commit a crime. Whereas a first generation hacker needed to write their code to perform attacks, new generations of hackers can now rely on scripts performing those tasks and controlled by automated processes. As technology makes it easier for anyone to perform more complex tasks, the skills a hacker requires to commit a crime decrease.

The reskilling effect

The impact of technology upon cybercrimes

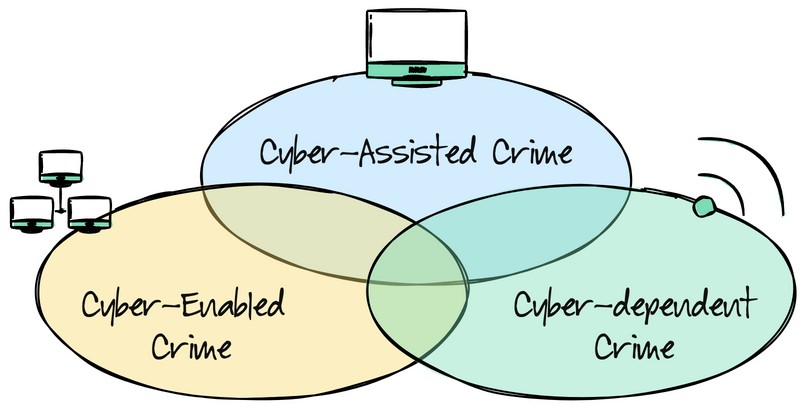

The genesis of cybercrimes originates in early computer crimes before their subsequent transformation by networking over two generations. By placing cybercrimes within a framework of time rather than space, we can understand them as successive generations defined by different states of technological development, with each transforming criminal opportunity.

This approach also helps us to quickly differentiate the technology between crimes and identify the applicable subject area of criminology.

| Feature | Cyber-Assisted Crime | Cyber-Enabled Crime | Cyber-Dependent Crime |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependence on technology | Low | Medium | High |

| Technology role | Supportive tool | Amplifies scope or reach | Core to the crime; impossible without it |

| Offline Possibility | Fully possible without tech | Possible but less impactful | Not possible without tech |

| Examples | Planning burglary using GPS | Phishing, romance scams, online fraud | Hacking, ransomware, botnets, DDoS |

| Primary Victim Type | Individuals or physical targets | Individuals, business (via Internet) | Digital infrastructure, systems, or data |

The first generation of cybercrime

The first generation of cybercrime used technology to assist traditional criminal behaviour. Initially, these behaviours occurred within computer systems that exploited mainframe computers and their operating systems. They mainly focused on the acquisition of money or the destruction or appropriation of restricted information. The first generation of cybercriminals differs from conventional criminal opportunity because the scope and volume of their activity could be executed with a computer.

The second generation of cybercrime

The second generation of cybercrimes is those committed across the network. Mainly driven by hackers and crackers, they were the product of the skills of early computer operators and the communication skills of phone phreakers (like Kevin Mitnick) who imaginatively cracked phone systems to make free telephone calls. The second generation of cybercrimes is mostly hybrid or adaptive, such as illegal Internet trading on the dark web, including explicit materials, scams, and fraudulent activity. Policing agencies are aware of this type of crime, and their problem in prosecuting it is related to trans-jurisdictional procedures.

The third generation of cybercrime

The third generation of cybercrimes is wholly dependent upon digital and networked technologies and is characterized by the Internet’s distributed and automated nature. These crimes started with the replacement of dial-up modems and the spread of broadband around the world. These new attacks rely less on social engineering and more on technology. The result is that the entry level for hackers has risen, and the hacking process has been automated into component services that can now be hired. This cybercrime is solely the product of opportunities created by the Internet and can only be perpetrated within cyberspace, even if some of its effects may fall outside of it.

At the extreme end of cyber-dependent crimes lie the more controversial harms, such as cyber-rape, cyber-bullying, cyber-hate, and the virtual vandalism of virtual worlds.

The new stakes of cybercrime

Between the mid-2000s and today, the volume of data theft has massively increased as data has become valuable. Data is the focus of many modern cybercrimes. In 2020, for example, it was estimated that 37 billion personal records had been exposed by hackers. Hackers are now targeting the databases of larger corporations, so the sheer volume of stolen data has increased.

The cybercrime agenda has changed, and the culture of fear that once surrounded hacking has transferred to the fear that our personal information, given in good faith, can now be used against us. In addition, there has been an increase in the appropriation of intellectual properties, which tend to fall outside the jurisdiction and experience of the criminal justice process.