In the months leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, a bizarre rumour began spreading across fringe corners of the internet. The claim? A Washington, D.C. pizza restaurant, Comet Ping Pong, was the center of a child-trafficking ring allegedly run by members of Hillary Clinton’s campaign. The theory, quickly dubbed “Pizzagate”, originated on anonymous forums, spread through social media at lightning speed, and culminated in real-world violence.

A Perfect Storm of Misinformation

Pizzagate emerged from a combination of:

- Leaked emails published by WikiLeaks from the Democratic National Committee, which conspiracy theorists scoured for “coded language.”

- 4chan and Reddit threads, where users speculated that references to “pizza” were actually code for child abuse.

- Amplification by influencers and fake news sites, which packaged these speculations into viral “articles” that looked like investigative exposés.

From keyboards to gunfire

The consequences became chillingly real on December 4, 2016, when Edgar Maddison Welch, a man from North Carolina, entered Comet Ping Pong armed with an AR-15 rifle, convinced he was rescuing trafficked children. He fired three shots inside the restaurant. miraculously injuring no one, before surrendering to police. Welch later admitted he had been misled by online posts, calling himself “foolish.”

This incident demonstrated, perhaps for the first time at such a scale, how a digital conspiracy could manifest as a real-world terrorist act motivated entirely by disinformation.

Platforms’ Role and the Early Era of Deplatforming

Pizzagate tested the limits of online moderation in many ways.

- Reddit banned the main Pizzagate subreddit for “personal information doxxing.”

- Twitter removed key hashtags after they became hubs for coordinated harassment.

- Facebook began experimenting with fact-checking partnerships and labeling false news.

The Anatomy of a Viral Conspiracy

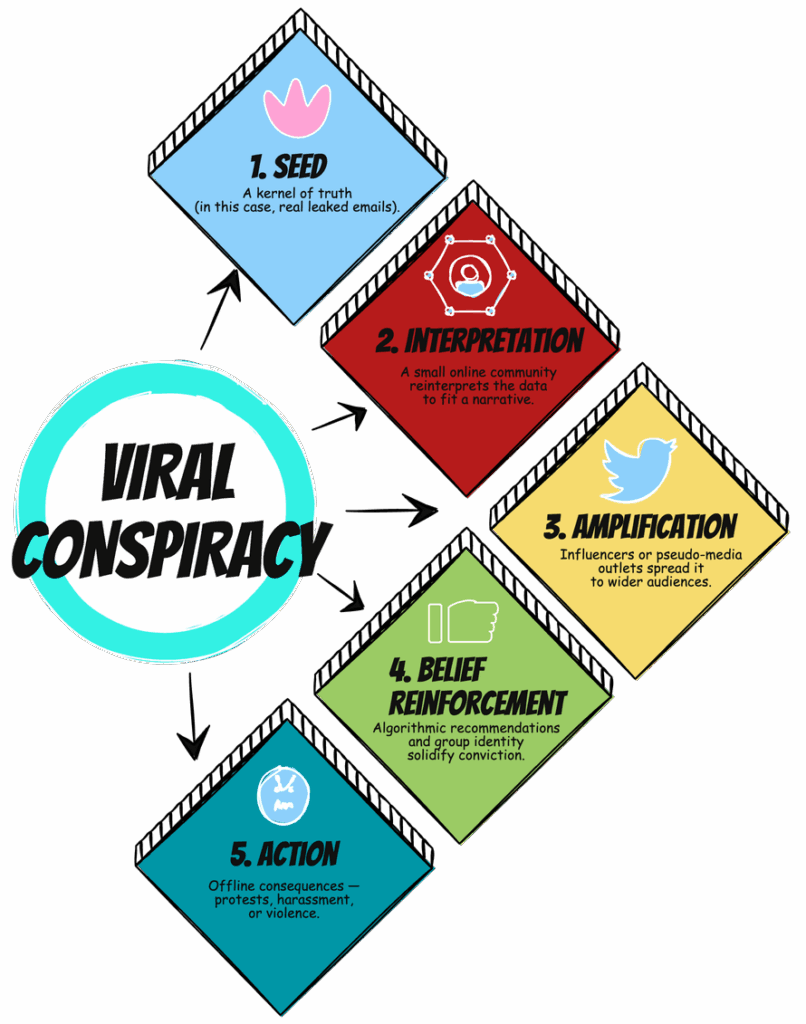

Pizzagate’s success followed a now-familiar pattern:

This sequence provides a model for how misinformation ecosystems function across platforms, one that analysts can quantify through social network mapping and temporal activity graphs.

Aftermath and Legacy

Though debunked, Pizzagate didn’t disappear: it mutated. Many of its promoters later adopted the broader QAnon narrative, framing Pizzagate as “the first revelation.”

By 2020, QAnon groups were recycling its imagery and slogans, suggesting that Pizzagate was the prototype of the modern conspiracy industrial complex.

It also permanently altered how law enforcement, journalists, and tech platforms handle online radicalization. The FBI’s 2019 bulletin explicitly listed “conspiracy-driven extremism” as a domestic terrorism concern, a category into which Pizzagate neatly fits.

Lessons learnt

Pizzagate’s endurance underscores several truths, the first of which is that misinformation is resilient. Once internalized, facts alone rarely undo belief. Another truth is that narrative simplicity beats complexity: “evil elites hiding in plain sight” is more gripping than nuanced political corruption. Finally, platform design matters: virality amplifies emotion, not accuracy.

For digital investigators and cybersecurity professionals, Pizzagate remains a case study in information operations, showing how digital forensics, behavioural analysis, and social-media monitoring can intersect with public safety.

What's left of Pizzagate

Today, Comet Ping Pong remains open, but its staff and owners still face occasional harassment. The gunman, Welch, is serving a four-year sentence. The story, however, lives on — evolving, merging, and resurfacing in new guises every election cycle.

Ultimately, Pizzagate reminds us that a single falsehood, if emotionally powerful enough, can become a movement.