We often hear about the importance of privacy and how crucial it is to keep our personal data and information safe. However, there are cases where our right to privacy is superseded by more pressing matters, such as national security, emergencies, or intelligence gathering programs. In the world, mass intelligence programs have been proliferating since the 1940s, sparking debate about their legitimacy. Here is what you need to know about them.

What is mass surveillance?

- Mass surveillance is the broad and systematic monitoring of a population, often without their knowledge or consent, to gather information and potentially control or influence behaviour. This practice is typically carried out by governments or corporations, and it can involve various forms of data collection, including communications, location data, and online activity.

How is mass surveillance different than intelligence?

- Mass surveillance involves monitoring a large segment of a population, rather than focusing on specific individuals or groups.

- It encompasses the collection of vast amounts of data, often through various means, such as phone records, internet activity, CCTV footage, and even biometric data.

- The purported aims of mass surveillance include national security, crime prevention, and social control, but it can also be used for commercial purposes or to gather intelligence.

- Mass surveillance raises significant ethical and legal concerns, particularly regarding privacy rights, freedom of expression, and the potential for abuse of power.

Common techniques used in mass surveillance activities

- Telecom interception (IMSI catchers, DPI)

- Internet metadata and packet collection

- CCTV + facial recognition

- Social media scraping & keyword tracking

- Use of commercial spyware (e.g., Pegasus, Predator, FinFisher)

- Real-time keyword flagging (e.g., "protest," “VPN”)

- Automated flagging systems for social credit or dissent

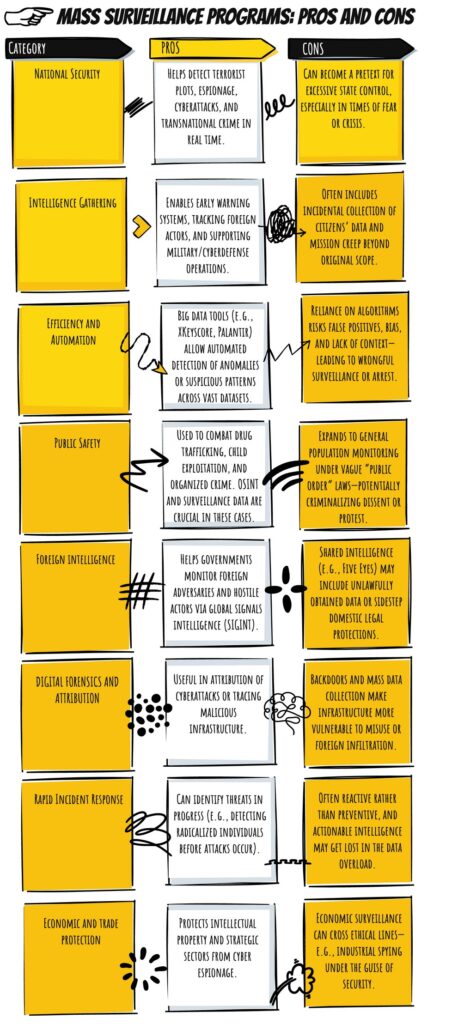

From a technical and operational standpoint, all the advantages brought by mass surveillance activities can also be weaponized.

For example, metadata collection is lightweight, scalable, and informative for pattern analysis. However, this data can be de-anonymized easily and used to build detailed social graphs.

Data retention assists forensic investigations by keeping historical logs, but it also becomes a honeypot for hackers. And while interception helps monitor hostile actors (e.g., cybercriminals, spies), it opens the door to abuse by insiders or vendors with access.

Pros and cons of mass surveillance

How it started: The Five Eyes Alliance and the Echelon Program

The first attempts at sharing intelligence date back to the Cold War. In 1946, the US and the UK signed an agreement to create the Five Eyes alliance.

Between the 1950s and the 1960s, the Five Eyes countries developed the Echelon program. This is a signals intelligence (SIGINT) network for global communications interception. Its original focus was Cold War espionage, but it was later expanded to economic intelligence, diplomatic spying and anti-terrorism. Echelon uses massive satellite and cable interception globally.

With time, the Five Eyes alliance expanded to Nine Eyes and Fourteen Eyes, now also involving France, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Belgium, Italy, and Spain.

First attempts at regulating mass surveillance

In the 1970s, the United States saw the first attempts at regulating and controlling mass surveillance activities. In 1975, the Church Committee started investigating abuses by intelligence agencies. As a result, in 1978, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) was enacted to regulate surveillance inside the U.S.

The expansion after 9/11

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 triggered the rapid expansion of surveillance. In October 2001, the USA PATRIOT Act was signed into law. Section 215 allows bulk collection of phone records (metadata).

In 2007, the PRISM program began under the Protect America Act and later the FISA Amendments Act (2008).

The PRISM Program

The purpose of PRISM was to collect data from major tech companies to monitor foreign communications under the FISA Act. That entailed direct access to the servers of companies such as Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Apple, Yahoo, Skype, YouTube, and more. The target of the data collection is non-U.S. citizens outside the United States, even if U.S. citizens’ data can be incidentally collected in the process. The data collection interests emails, video chats, photos, stored data, VoIP, file transfers and more.

The tech companies involved deny direct access to their servers and claim compliance under legal obligation. PRISM has raised concerns over time in regards to the Fourth Amendment (unreasonable searches).

PRISM is an ongoing program, but it was exposed in 2013 by Edward Snowden.

The Edward Snowden Leaks

- XKeyscore, a global internet surveillance tool for real-time data search and analysis. It can search and analyze nearly everything a user does online: Emails, browsing history, social media, metadata, content. The program requires minimal justification to access data. It also has a vast data retention with worldwide sources.

- TEMPORA, a UK fiber cable tapping program. This program stores bulk metadata and content for up to 30 days. The data is shared with the NSA. It claimed to collect data from 600 million communications per day.

- MUSCULAR, a joint NSA-GCHQ data center infiltration program. Infiltrates Google and Yahoo data centers (without company knowledge). The program captured data in transit between data center locations and bypassed encryption by tapping directly into internal cables.

- Boundless Informant, an NSA metadata visualization program.

- Ballrun, a decryption weakening program.

The Upstream collection program

Similarly to the MUSCULAR program, the NSA started its own data interception program from fiber-optics cables and Internet infrastructure in North America, tapping into sources such as telecommunications companies (AT&T, Verizon, etc.) and international Internet backbone providers. Its mission is the bulk collection of internet traffic (emails, chats, VoIP, etc.) as it moves through the global internet. It includes programs like FAIRVIEW, BLARNEY, and STORMBREW.

The public's reaction

The Snowden’s leaks sparked a massive outcry after their revelations. As a result, countries and companies increased their focus on encryption, privacy laws, and whistleblower protection programs.

However, Europe and North America are not the only areas in the world carrying out mass surveillance programs.

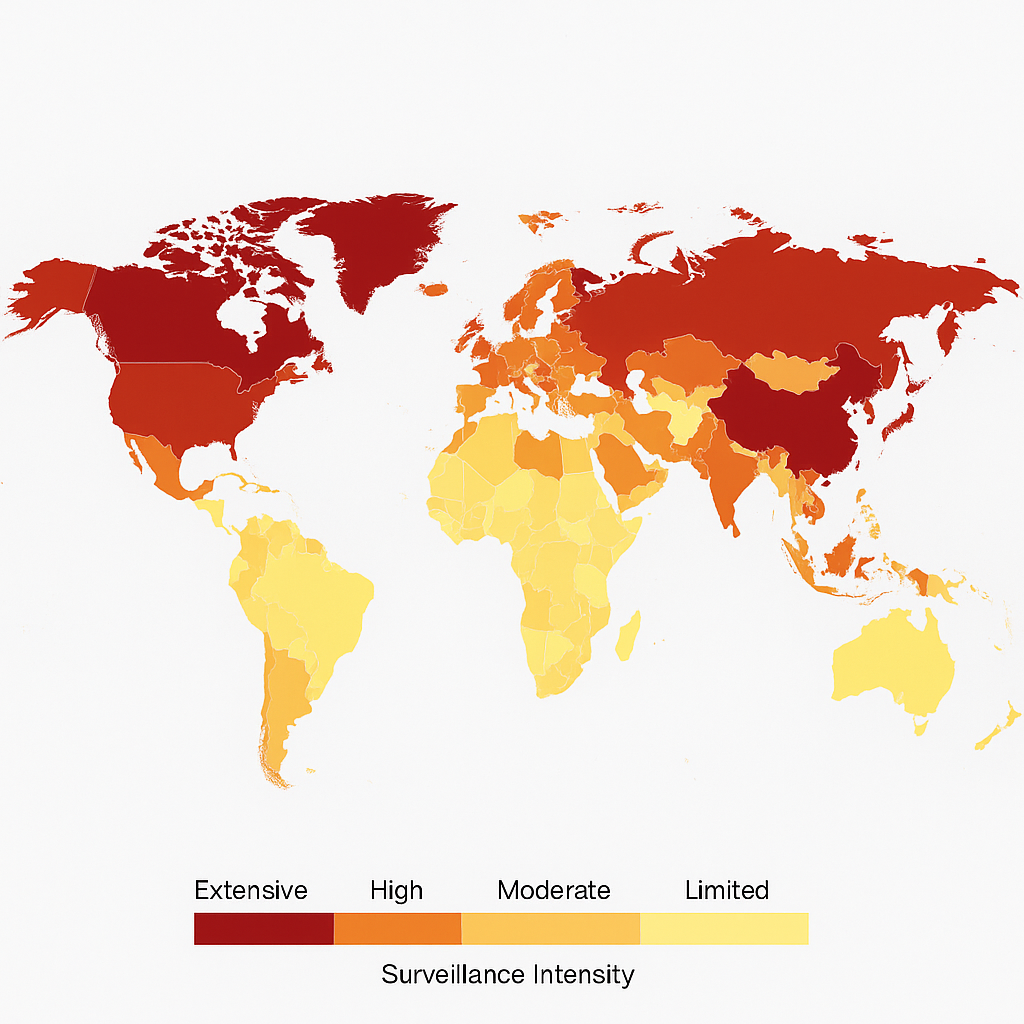

A map of mass surveillance programs

The following map shows the world’s countries based on the intensity of their mass surveillance programs, taking into account the existing (known) alliances.

* Note: On this map, Canada is similarly compared to China as per the intensity of their mass surveillance programs. The map is a simplified abstraction. It likely ranks Canada and China similarly based on volume of surveillance infrastructure, Canada’s participation in Five Eyes, and the use of sophisticated technical tools for interception and analytics. However, equating them in practice is misleading. Key differences lie in their legal oversight, intent, public awareness and recourse.

Mass surveillance in China

- Skynet: 600+ million CCTV cameras, facial recognition, and AI analytics.

- Sharp eyes: it extends Skynet to rural areas and neighbourhoods.

- Social credit system: it tracks citizen behaviour and assigns scores based on services.

- Great Firewall: it monitors and filters Internet content and performs deep packet inspection.

Mass surveillance in Russia

Russia has state-mandated telecom and internet monitoring. Among their key programs are:

- SORM (System for Operative Investigative Activities): it requires all ISPs to install interception equipment. Under this program, law enforcement can monitor Internet, SMS, and calls in real time without a court order.

- Yarovaya Law (2016): it requires storage of all user communications and metadata for six months to three years and mandatory decryption by service providers.

Mass surveillance in Iran

Iran heavily filters and monitors internet access. They use Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) to throttle/block content and encourage the creation of domestic internet infrastructure to isolate users.

Mass surveillance in Turkey

In Turkey, the Information Technologies and Communication Authority (BTK) can access metadata and user traffic. This has been used in the past for crackdowns on journalists and dissidents, also involving the use of spyware and mass surveillance tools. Turkey also has centralized surveillance of mobile and internet providers.

Mass surveillance in India

India implements large-scale interception with limited legal transparency. Its key programs are:

- CMS (Central Monitoring System): it allows access to phone, mobile, and Internet traffic without requiring telecom involvement.

- NETRA (Network Traffic Analysis): it allows real-time interception of emails, VOIP, and blog posts.

- NATGRID: it links intelligence agencies with data from 21 organizations, including banks, travel, telecom, etc.)

Mass surveillance in Saudi Arabia and the UAE

Saudi Arabia and the Emirates use the Pegasus spyware and other state hacking tools to surveil journalists, activists, and foreign dissidents. Internet usage is monitored and anonymity discouraged. In the Emirates, former NSA contractors have been tied to programs such as Karm and Project Raven.

Mass surveillance in Egypt

In Egypt, there is deep surveillance of encrypted traffic, social media, and messaging apps. Egypt has used URL filtering, DPI and phishing against dissidents, and the legislation criminalizes spreading “false information,” used to target political opposition.

Mass surveillance in Singapore

Singapore operates under a preventive law model (ISA), allowing detention and surveillance without court oversight. There is a widespread use of surveillance cameras, facial recognition, and internet monitoring in public spaces. Their Smart Nation program links data from citizens’ devices, infrastructure, and services.

Mass surveillance in the European Union

- France: the Surveillance Law of 2015 permits the bulk collection of metadata without judicial oversight.

- Germany: BND (the German foreign intelligence agency) is allowed to monitor non-German citizens' communications.

- Poland and Hungary: both countries use mass surveillance against civil society, journalists, and opposition figures.

- Italy: the Garante agency uses centralized traffic monitoring and authorizes interception by the judiciary.

The Schrems II ruling in 2020 invalidated the EU–US Privacy Shield, citing lack of protection from U.S. mass surveillance and highlighting ongoing global concern.

Mass surveillance in Brazil

Brazil has taken a dual stance: on one side, they promoted internet rights (Marco Civil da Internet), but they also enabled metadata collection in criminal investigations, and worked with U.S. intelligence in the past (as revealed by the Snowden leaks).

Mass surveillance: Do we need it and is it worth it?

From an ethical and social point of view, mass surveillance programs require a number of trade-offs:

- Security or Privacy? Surveillance can prevent harm and save lives. However, it undermines the right to privacy, potentially turning every citizen into a suspect.

- Trust or distrust the Government? Transparent programs may boost trust through protection. However, secretive programs (e.g., PRISM, ECHELON) erode public trust when leaked.

- Innovation or freedom of expression? Tools developed for surveillance (e.g., AI, facial recognition) may benefit other sectors. However, mass surveillance can chill free expression, journalism, and political activity.

- Leeway or accountability? With judicial and legislative oversight, it can be constrained and targeted. Without strong oversight, it risks enabling authoritarian drift even in democracies.

Surveillance may be defensible when it is proportionate (focused on specific national security or criminal threats), legal (backed by judicial authorization, oversight, and review), and transparent (with meaningful public accountability such as audits and reports. It’s up to each country and its citizens to find the right balance.